The History Of Rover Car Company

In the wake of fostering a layout for the cutting edge bike with its Rover Safety Bicycle of 1885, the organization moved into the car business. It began building bikes, then vehicles, utilizing the Viking Longship identification from 1904. After World War II, Land Rover vehicles were created and added to the Rover range. Puma Land Rover, an auxiliary of Indian-based Tata, has claimed the Rover brand starting around 2008.

In the mid 1880s, cycles were famous, however perilous, given the level of the accelerating saddle on penny-farthings and high-wheel tricycles.

J K Starley impacted the world forever in 1885, by delivering the Rover Safety bike – a back tire chain-driven cycle with two comparative estimated wheels, making it more steady than the past high-wheel plans. The Rover Cycle Company Ltd was conceived.

Starley then fitted a Peugeot motor to a Rover bike and an Edwell Parker electric engine to a tricycle, however kicked the bucket unexpectedly from the get-go in October 1901 matured 46 and the business was taken over by business visionary Harry Lawson.

The organization created the Rover Imperial cruiser in November 1902 and resulting Rover bikes sold well, totalling in excess of 10,000 when creation stopped in 1924.

|

|

In 1904, Rover started creating cars, beginning with the two-seater, single-chamber Rover Eight, planned by Edmund Lewis, who came from Daimler, where Lawson had worked. The vehicle highlighted cast-aluminum parts, including its spine undercarriage.

|

|

The following Rover was an all the more traditionally outlined, 6hp, cheaper vehicle, trailed by Lewis-planned four-chamber 10/12 and 16/20 models. The last’s 3.2-liter had sufficient snort to win the 1907 Tourist Trophy race.

Lewis passed on the organization to join Deasy in late 1905.

In 1908, Bernard Wright planned the twin-chamber Rover 12 and 2.4-liter, four-chamber 15. Sleeve-valve motors were new in 1910, when Wright concocted 1.1-liter, single-chamber, 8hp and 1.9-liter, twin-chamber, 12hp sleeve-valve-fueled models. The motor sizes propose some Daimler inclusion.

|

|

Wright left after the sleeve-valve explore didn’t function admirably and he was supplanted by Owen Clegg, who joined from Wolseley and set about changing the item range.

The 12hp model was presented in 1912 and was controlled by a 2.3-liter, four-chamber, side-valve motor. This vehicle was fruitful to the point that any remaining vehicles were dropped and, for some time, Rover sought after a ‘one model’ strategy.

Similarly as with past Rover planners, Clegg’s term was short and he left in 1912, to join the French auxiliary of Darracq and Company, London.

During the World War I, Rover made bikes, including 499cc single-chamber cruisers to the Russian Army, trucks to Maudslay plans and, not having their very own reasonable one, ambulances to a Sunbeam plan.

After the War, creation of the 12hp model continued and it was participated in 1920 by another 8hp model, fueled by a level twin, one-liter motor planned by J Y Sangster, who went on the become one Britain’s pre-famous bike originators.

|

1924 Rover 8 – Martin Pettit

|

This virtual cyclecar demonstrated famous, with nearly 17,000 delivered before it was supplanted in 1924 by another 9/20hp model.

In 1923, new Rover creator, Mark Wild, concocted the 14, to supplant the fruitful 12. A 3.4-liter, six-chamber model disappointed.

The 9/20 was overhauled in 1927 to the 10/25. The drag was expanded by just 3mm, however retuning the motor gave it 25-percent more power.

One more new originator, Peter August Poppe, put into creation at Rover his generally finished plan for another two-liter vehicle that turned into the Rover 14/45.

|

|

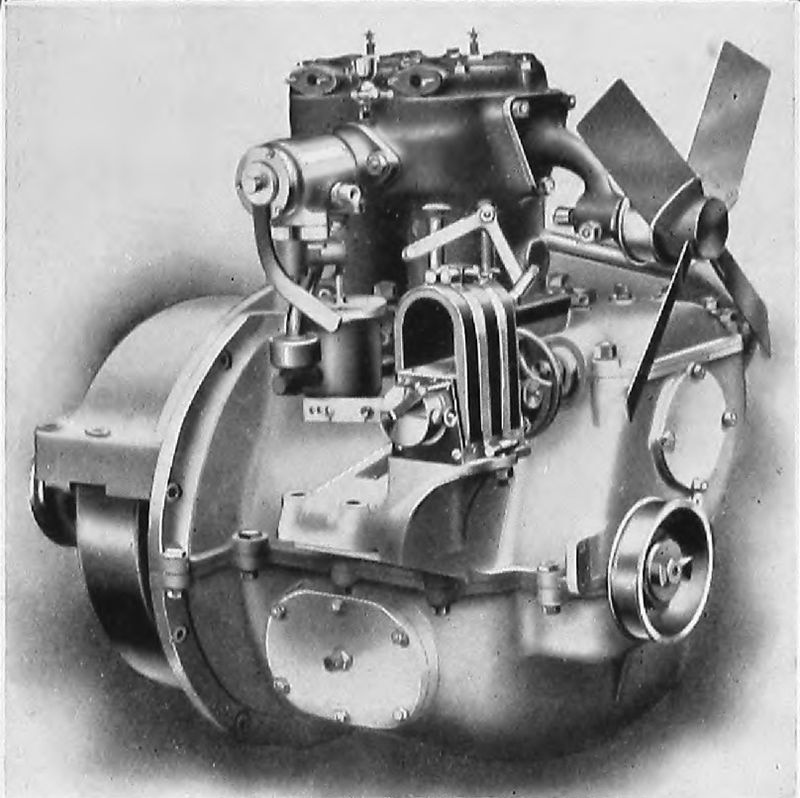

Poppe’s new single-above camshaft, 2.1-liter motor had hemispherical burning chambers, with slanted valves and halfway found flash attachments. The camshaft worked straightforwardly on the bay valves and, through level pushrods, worked the fumes valves on the opposite side of the motor. The camshaft was driven by an upward shaft at the back of the motor.

(BMW might have inspected this Rover motor plan, on the grounds that the effective 328 motor utilized a very much like valve-working plan.)

The 14/45 was entirely agreeable, yet weighty and considered underpowered. In the span of a year Rover had added a 2.4-liter, 16/50 to the reach, however these OHC Rovers were costly to construct and not well known with clients. Something like 2,000 were constructed.

Poppe’s worked on arrangement was a 45hp, above valve, two-liter straight-six that turned into the groundwork of all Rover motors until 1948.

|

|

The business was not exceptionally effective during the 1920s and didn’t deliver a profit from 1923 until the mid-1930s. During 1928 Frank Searle was designated overseeing chief to regulate recuperation. On his suggestion Spencer Wilks was acquired from Hillman as senior supervisor and was designated to the board in 1929.

|

|

Poppe’s last motor plan fueled the 1929 Light Six that was fitted with a lightweight, texture body, authorized from Weymann. Despite the fact that it had a similar result as the 14/45 it gauged significantly less and had much better execution.

The Rover Light Six won consideration when it was the primary effective member in the Blue Train Races – a progression of record-breaking endeavors among cars and trains in the last part of the 1920s and mid 1930s. It saw various drivers and their own or supported vehicles race against the Le Train Bleu, a train that ran among Calais and the French Riviera.

Many had previously bombed this test, yet previous cruiser analyzer and trailblazer marketing specialist Dudley Noble knew that the typical speed of the Blue Train, with its stops considered, was something like around 40 mph (64 km/h). To beat the train, Noble drove pretty much relentless from St Raphael to Calais.

The Rover Light Six found the middle value of 38mph (61km/h) on its 750-mile (1210-km) venture and gave the Rover a 20-minute lead over the train. The Blue Train had been beaten interestingly and the Rover group was commended by the Daily Express.

In 1930 the Light Six was supplanted by the Light twenty, with a bigger, 2.6-liter variant of the OHV motor that put out 60hp.

Simultaneously, the 10/25 had the choice of an all-steel body, made by the Pressed Steel Company. This was a similar body as utilized on the Hillman Minx. Preceding this time Rover had been an incredible ally of the extremely light Weymann bodies that went unexpectedly out of design with the interest for sparkling coachwork and more bended body shapes. Weymann bodies stayed in the plant list until 1933.

|

|

Likewise, Searle split Midland Light Car Bodies from Rover with an end goal to set aside cash and taught Robert Boyle and Maurice Wilks to plan another little vehicle.

This was the Rover Scarab, with a back mounted, V-twin-chamber, air-cooled motor. Declared in 1931, a van form was displayed at Olympia, yet it didn’t go into creation. (It might seem to be Rover spearheaded a plan that one more German organization, VW, profited by, however the two organizations truly replicated the Czech creator, Tatra.)

Forthcoming Searle and Spencer Wilks set about redesigning the organization and moving it upmarket. In 1930 Spencer Wilks was joined by his sibling, Maurice, who had additionally been at Hillman as boss architect. Spencer Wilks remained with the organization until 1962 and his sibling, until 1963. Forthright Searle left the board toward the finish of 1931.

The Wilks Brothers laid out Rover as an organization with a few European illustrious, blue-blooded and legislative warrants, and upper-working class and star clients.

|

|

Meanderer had shown benefits in 1929 and 1930, however with the financial slump in 1931 and 1932, Rover detailed misfortunes and recently set up get together activities in Australia and New Zealand were shut after under two-years activity.

Meanderer got back to benefit in 1933, yet the Australasian tasks weren’t continued, apparently in light of the fact that it had been understood that UK-market Rovers required costly revising to contend with North American obtained vehicles Down Under.

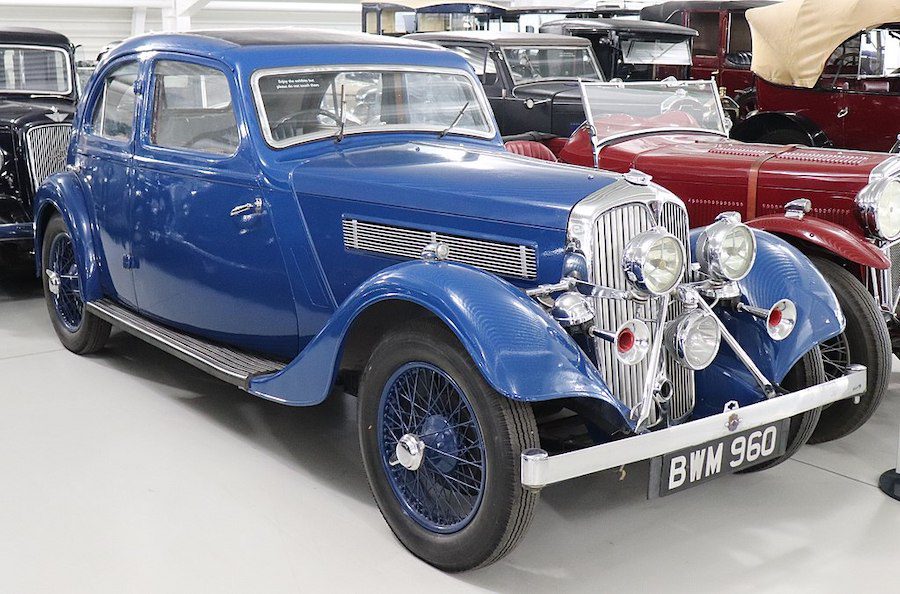

Creation of a significantly updated trade for Rover’s 16hp Meteor was continued under the name Rover 16 in mid-1936 and, with a hole for World War II, the 16 stayed in Rover’s list until mid 1948.

|

|

In the last part of the 1930s, as the War mists accumulated over Europe, Rover set up an air motor and airframe producing manufacturing plant, with British Government finance, at Solihull, in 1940. Both were utilized making air motors and airframes.

Likewise in 1940, Rover was moved toward by Frank Whittle to create and deliver Whittle’s stream motor, which it accomplished for a period. Notwithstanding, Rover had its own stream turbine plan and gave over its part in the fly motor venture to Rolls-Royce, in return for the last’s Meteor tank motor production line.

(The Meteor motor was supplanted for new tanks in 1962, and as Rover needed seriously fabricating limit with regards to the Land Rover, they moved the production of Meteor spare parts for the British and different states back to Rolls-Royce.)

|

|

Solihull turned into the new community for Rover vehicles, when creation continued in 1947, with the Rover 12 Sports Tourer. Notwithstanding, the Land Rover and its Range Rover subsidiaries turned into an out of control a positive outcome and were the organization’s greatest dealers from the 1950s. (We’ll cover the LandRover story in a different story, due in September 2021.)

|

|

The Rover Sixty and Rover Seventy-Five, or Rover P3, series were 1.6-liter and 2.0-liter chief vehicles delivered in February 1948 and created until the mid year of 1949.

The Rover P4 series was planned by Gordon Bashford and delivered from 1949 until 1964. Model deliveries started with the six-chamber, 2.1-liter Rover 75, continued in 1953 by the 2.0-liter, four-chamber Rover 60 and the 2.6-liter, six-chamber Rover 90. These motors were F-head, gulf over-exhaust-valve types.

|

|

The P4 vehicles were refined however grave and became known as the ‘Aunt’ Rovers.

The P4 series was enhanced in September 1958 by a new, safely molded, Rover 3.0-liter P5 that covered the P4 for a considerable length of time.

The P5 was a huge extravagance cantina, fueled by a three-liter variant of Rover’s six-chamber motor, conveyed forward from the P4 series. It was the principal Rover vehicle with unitary bodywork, styled by David Bache. This model had a conventional, very much designated inside.

|

|

In 1962 came the saucy four-entryway roadster variant, with a brought down rooftop line and both car and car scored an updated motor, with 129hp. Power went up to 134hp in 1965.

Meanderer sent off its P6, little, elite execution, T2000 cantina in 1965, fueled by a new, above camshaft, four-chamber, two-liter motor that at first put out 104hp, yet before long was worked on the 124hp by the expansion of twin SU carburettors.

|

|

The 3.5-liter V8 P5 models of 1967 utilized an all-aluminum V8 ‘BOP’ motor plan bought from General Motors. The 3.0-and 3.5-liter models became top choices for transport of dignitaries, including British Prime Ministers from Harold Wilson to Margaret Thatcher. HM The Queen additionally involved a few Rover P5 vehicles for her confidential motoring.

The more modest P6 got the 3.5-liter motor, in 1968, in light of the fact that its aluminum development implied it gauged something like the iron four.

While these updated Rover items were being delivered in 1967/68 and Land Rover deals were soaring all over the planet, Rover turned out to be essential for the Leyland Motor Corporation (LMC), which previously possessed Triumph and soon, LMC converged with British Motor Holdings (BMH) to turn into the British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC). It probably appeared to be smart at that point, however it was the start of the end for the free Rover Company.

|

|

Having bought the Alvis organization in 1965, Rover had been dealing with a V8-controlled supercar to sell under the Alvis name, as well as a redesigned P6, known as the P8, for which tooling had proactively been bought. Notwithstanding, the BLMC brand assortment implied that Rover and Jaguar were corporate accomplices, so these Rover projects were dropped, to forestall inner rivalry with Jaguar items.

BLMC was a major single objective for aggressor British associations and Solihull-based Rover’s legacy was polluted by the notorious modern relations and administrative issues that plague the British engine industry all through the 1970s.

Due to its no-contention reasoning, Rover kept on fostering its ‘100-inch Station Wagon’, which turned into the pivotal Range Rover, sent off in 1970.

The last evident Rover-planned vehicle was the classy and progressive SD1 that was sent off in 1976, fueled by the pervasive 3.5-liter V8. It was worked by the Specialist Division (later the Jaguar-Rover-Triumph division) of British Leyland (BL) and they ought to have been embarrassed about themselves. Fabricate quality was shocking.

The SD1 was showcased under different names and in 1977 it won the European Car of the Year title, yet ensuing press reports from Europe were accursing and trade vehicles were no more excellent. (Allan Whiting can recall driving a press vehicle from Sydney to Katoomba and, when he showed up at Mt Victoria, looked as the instrument binnacle tumbled off the highest point of the dashboard, hanging on its umbilical wiring. Pipe tape held it set up for the bring trip back!)

Likewise, the SD1 proceeded with Rover’s interest with confounded suspension that was problematic and terribly costly to fix.

The Sd1 was created from 1976 until 1986, when it was supplanted by the Rover 800 that owed a larger number of to Honda than to Rover.